This post is syndicated from rubin.io.

Welcome to day 12 of my Bitcoin Advent Calendar. You can see an index of all the posts here or subscribe at judica.org/join to get new posts in your inbox

Congestion is an ugly word, eh? When I hear it my fake synthesia triggers green slime feeling, being stuck in traffic with broken AC, and ~the bread line~ waiting for your order at a crowded restaurant when you’re super starving. All not good things.

So Congestion Control sounds pretty sweet right? We can’t do anything about the demand itself, but maybe we can make the experience better. We can take a mucinex, drive in the HOV lane, and eat the emergency bar you keep in your bag.

How might this be used in Bitcoin?

- Exchange collects N addresses they need to pay some bitcoin

- Exchange inputs into this contract

- Exchanges gets a single-output transaction, which they broadcast with high fee to get quick confirmation.

- Exchange distributes the redemption paths to all recipients (e.g. via mempool, email, etc).

- Users verify that the funds are “locked in” with this contract.

- Party

- Over time, when users are willing to pay fees, they CPFP pay for their redemptions (worst case cost \(O(\log N)\))

Throughout this post, we’ll show how to build the above logic in Sapio!

Talk Nerdy To Me

Let’s define some core concepts… Don’t worry too much if these are a bit hard to get, it’s just useful context to have or think about.

Latency

Latency is the time from some notion of “started” to “stopped”. In Bitcoin you could think of the latency from 0 confirmations on a transaction (in mempool) to 1 confirmation (in a block), which is minimally expected to be 10 minutes for high fee transactions, but could be longer depending on the other transactions.

Fairness

Fairness is a measure of how “equitable” a distribution of goods or services is. For example, suppose I want to divide 10 cookies among 10 children.

What if 1 child gets two cookies and the other 9 get 8/9ths of a cookie each? Or what if 1 child gets no cookie and the other 9 get 10/9ths of a cookie each? How fair is that?

Mathematicians and computer scientists love to come up with different measures of fairness to be able to quantatatively compare these scenarios and their relative fairness.

In Bitcoin we might think of different types of fairness: how long does your transaction spend in the mempool? How much fee did you pay?

Throughput & Capacity

Let’s spend another moment on fairness. Perfectly fair would be:

- All children get 1 cookie

- All children get 1/10th of 1 cookie.

- All children get 0 cookies.

Clearly only one of these is particularly efficient.

Thus, we don’t just want to measure fairness, we also want to measure the throughput against the capacity. The capacity is the maximum throughput, and the the throughput is essentially how many of those cookies get eaten (usually, over time). Now let’s look at our prior scenarios:

- All children get 1 cookie: Perfect Throughput.

- All children get 1/10th of 1 cookie: 1/10th Throughtput/Capacity.

- All children get 0 cookies: 0 Throughput :(

In this case it seems simple: why not just divide the cookies you big butt!

Well sometimes it’s hard to coordinate the sharing of these resources. For example, think about if the cookies had to be given out in a buffet. The first person might just take two cookies, not aware there were other kids who wouldn’t get one!

This maps well onto the Bitcoin network. A really rich group of people might do a bunch of relatively high fee transactions that are low importance to them and inadvertently price out lower fee transactions that are more important to the sender. It’s not malicious, just a consequence of having more money. So even though Bitcoin can achieve 1MB of base transaction data every 10 minutes, that capacity might get filled with a couple big consolidation transactions instead of many transfers.

Burst & Over Provisioning

One issue that comes up in systems is that users show up randomly. How often have you been at a restaurant with no line, you order your food, and then as soon as you sit down the line has ten people in it? Lucky me, you think. I showed up at the right time!. But then ten minutes later the line is clear.

Customers show up kind of randomly. And thus we see big bursts of activity. Typically, in order to accomodate the bursts a restaurant must over-provision it’s staff. They only make money when customers are there, and they need to serve them quickly. But in between bursts, staff might just be watching grass grow.

The same is true for Bitcoin. Transactions show up somewhat unpredictably, so ideally Bitcoin would have ample space to accomodate any burst (this isn’t true).

Little’s Law

Little’s law is a deceptively simple concept:

$$L = \lambda \times W$$

where \(L = \) length of the queue, \(\lambda = \) the arrival rate and \(W=\) the average time a customer spends in the system.

What’s remarkable about it is that it makes almost no assumptions about the underlying process.

This can be used to think about, e.g., a mempool.

Suppose there are 10,000 transactions in the mempool, and based on historical data we see 57 txns a minute.

$$ \frac{10,000 \texttt{ minutes}}{57 \texttt{ transactions per minute}} = 175 \texttt{ minutes}$$

Thus we can infer how long transactions will on average spend waiting in the mempool, without knowing what the bursts look like! Very cool.

I’m just showing off

I didn’t really need to make you read that gobbledygook, but I think they are really useful concepts that anyone who wants to think about the impacts of congestion & control techniques should keep in mind… Hopefully you learned something!

It’s Bitcoin Time

Well, what’s going on in Bitcoin land? When we make a transaction there are multiple different things going on.

- We are spending coins

- We are creating new coins

Currently, those two steps occur simultaneously. Think of our cookies. Imagine if we let one kid get cookies at a time, and they also have to get their milk at the same time. Then we let the next kid go. It’s going to take

$$ T_{milk} + T_{cookies} $$

To get everyone served. What if instead we said kids could get one and then the other, in separate lines.

Now it will take something closer to $$\max(T_{milk}, T_{cookies})$$.1 Whichever process is longer will dominate the time. (Probably milk).

Now imagine that getting a cookie takes 1 second per child, and getting a milk takes 30 seconds. Everyone knows that you can have a cookie and have milk after. If children take a random amount of time – let’s say on average 3 minutes, sometimes more, sometimes less – to eat their cookies, then we can serve 10 kids cookies in 10 seconds, making everyone happy, and then fill up the milks while everyone is enjoying a cookie. However, if we did the opposite – got milks and then got cookies, it would take much longer for all of the kids to get something and you’d see chaos.

Back to Bitcoin. Spending coins and creating new coins is a bit like milk and cookies. We can make the spend correspond to distributing the cookies and setting up the milk line. And the creating of the new coin can be more akin to filling up milks whenever a kid wants it.

What this means practically is that by unbundling spending from redeeming we can serve a much greater number of users that if they were one aggregate product because we are taking the “expensive part” and letting it happen later than the “cheap part”. And if we do this cleverly, the “setting up the milk line” in the splitting of the spend allows all receivers to know they will get their fair share later.

This makes the system much higher throughput (unlimited confirmations of transfer), lower latency to confirmation (you an see when a spend will eventually pay you), but higher latency to coin creation in the best case, although potentially no different than the average case, and (potentially) worse overall throughput since we have some waste from coordinating the splitting.

It also improves costs because we may be willing to pay a higher price for part one (since it generates the confirmation) than part two.

Can we build it?

Let’s start with a basic example of congestion control in Sapio.

First we define a payment as just being an Amount and an Address.

/// A payment to a specific address

pub struct Payment {

/// # Amount

/// The amount to send in btc

pub amount: AmountF64,

/// # Address

/// The Address to send to

pub address: Address,

}

Next, we’ll define a helper called PayThese, which takes a list of contracts

of some kind and pays them after an optional delay in a single transaction.

You can think of this (back to our kids) as calling a group of kids at a time (e.g., table 1, then table 2) to get their cookies.

struct PayThese {

contracts: Vec<(Amount, Box<dyn Compilable>)>,

fees: Amount,

delay: Option<AnyRelTimeLock>,

}

impl PayThese {

#[then]

fn expand(self, ctx: Context) {

let mut bld = ctx.template();

// Add an output for each contract

for (amt, ct) in self.contracts.iter() {

bld = bld.add_output(*amt, ct.as_ref(), None)?;

}

// if there is a delay, add it

if let Some(delay) = self.delay {

bld = bld.set_sequence(0, delay)?;

}

// pay some fees

bld.add_fees(self.fees)?.into()

}

fn total_to_pay(&self) -> Amount {

let mut amt = self.fees;

for (x, _) in self.contracts.iter() {

amt += *x;

}

amt

}

}

impl Contract for PayThese {

declare! {then, Self::expand}

declare! {non updatable}

}

Lastly, we’ll define the logic for congestion control. The basics of what is happening is we are going to define two transactions: One which pays from A -> B, and then one which is guaranteed in B’s script to pay from B -> {1…n}. This splits the confirmation txn from the larger payout txn.

However, we’re going to be a little more clever than that. We’ll apply this principle recursively to create a tree.

Essentially what we are going to do is to take our 10 kids and then divide them

into groups of 2 (or whatever radix). E.g.: {1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10} would become

{ {1,2}, {3,4}, {5,6}, {7,8}, {9,10} }. The magic happens when we recursively

apply this idea, like below:

{1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10}

{ {1,2}, {3,4}, {5,6}, {7,8}, {9,10} }

{ { {1,2}, {3,4} }, { {5,6}, {7,8} }, {9,10} }

{ { {1,2}, {3,4} }, { { { 5,6}, {7,8} }, {9,10} } }

{ { { {1,2}, {3,4}}, { { {5,6}, {7,8} }, {9,10} } } }

The end result of this grouping is a single group! So now we could do a transaction to pay/give cookies to that one group, and then if we wanted 9 to get their cookie/sats We’d only have to publish:

level 0 to: Address({ { { {1,2}, {3,4} }, { { {5,6}, {7,8} }, {9,10} } } })

level 1 to: Address({ { {5,6}, {7,8} }, {9,10} } })

level 2 to: Address({9,10})

Now let’s show that in code:

/// # Tree Payment Contract

/// This contract is used to help decongest bitcoin

//// while giving users full confirmation of transfer.

#[derive(JsonSchema, Serialize, Deserialize)]

pub struct TreePay {

/// # Payments

/// all of the payments needing to be sent

pub participants: Vec<Payment>,

/// # Tree Branching Factor

/// the radix of the tree to build.

/// Optimal for users should be around 4 or

/// 5 (with CTV, not emulators).

pub radix: usize,

#[serde(with = "bitcoin::util::amount::serde::as_sat")]

#[schemars(with = "u64")]

/// # Fee Sats (per tx)

/// The amount of fees per transaction to allocate.

pub fee_sats_per_tx: bitcoin::util::amount::Amount,

/// # Relative Timelock Backpressure

/// When enabled, exert backpressure by slowing down

/// tree expansion node by node either by time or blocks

pub timelock_backpressure: Option<AnyRelTimeLock>,

}

impl TreePay {

#[then]

fn expand(self, ctx: Context) {

// A queue of all the payments to be made initialized with

// all the input payments

let mut queue = self

.participants

.iter()

.map(|payment| {

// Convert the payments to an internal representation

let mut amt = AmountRange::new();

amt.update_range(payment.amount);

let b: Box<dyn Compilable> =

Box::new(Compiled::from_address(payment.address.clone(),

Some(amt)));

(payment.amount, b)

})

.collect::<VecDeque<(Amount, Box<dyn Compilable>)>>();

loop {

// take out a group of size `radix` payments

let v: Vec<_> = queue

.drain(0..std::cmp::min(self.radix, queue.len()))

.collect();

if queue.len() == 0 {

// in this case, there's no more payments to make so bundle

// them up into a final transaction

let mut builder = ctx.template();

for pay in v.iter() {

builder = builder.add_output(pay.0, pay.1.as_ref(), None)?;

}

if let Some(timelock) = self.timelock_backpressure {

builder = builder.set_sequence(0, timelock)?;

}

builder = builder.add_fees(self.fee_sats_per_tx)?;

return builder.into();

} else {

// There are still more, so make this group and add it to

// the back of the queue

let pay = Box::new(PayThese {

contracts: v,

fees: self.fee_sats_per_tx,

delay: self.timelock_backpressure,

});

queue.push_back((pay.total_to_pay(), pay))

}

}

}

}

impl Contract for TreePay {

declare! {then, Self::expand}

declare! {non updatable}

}

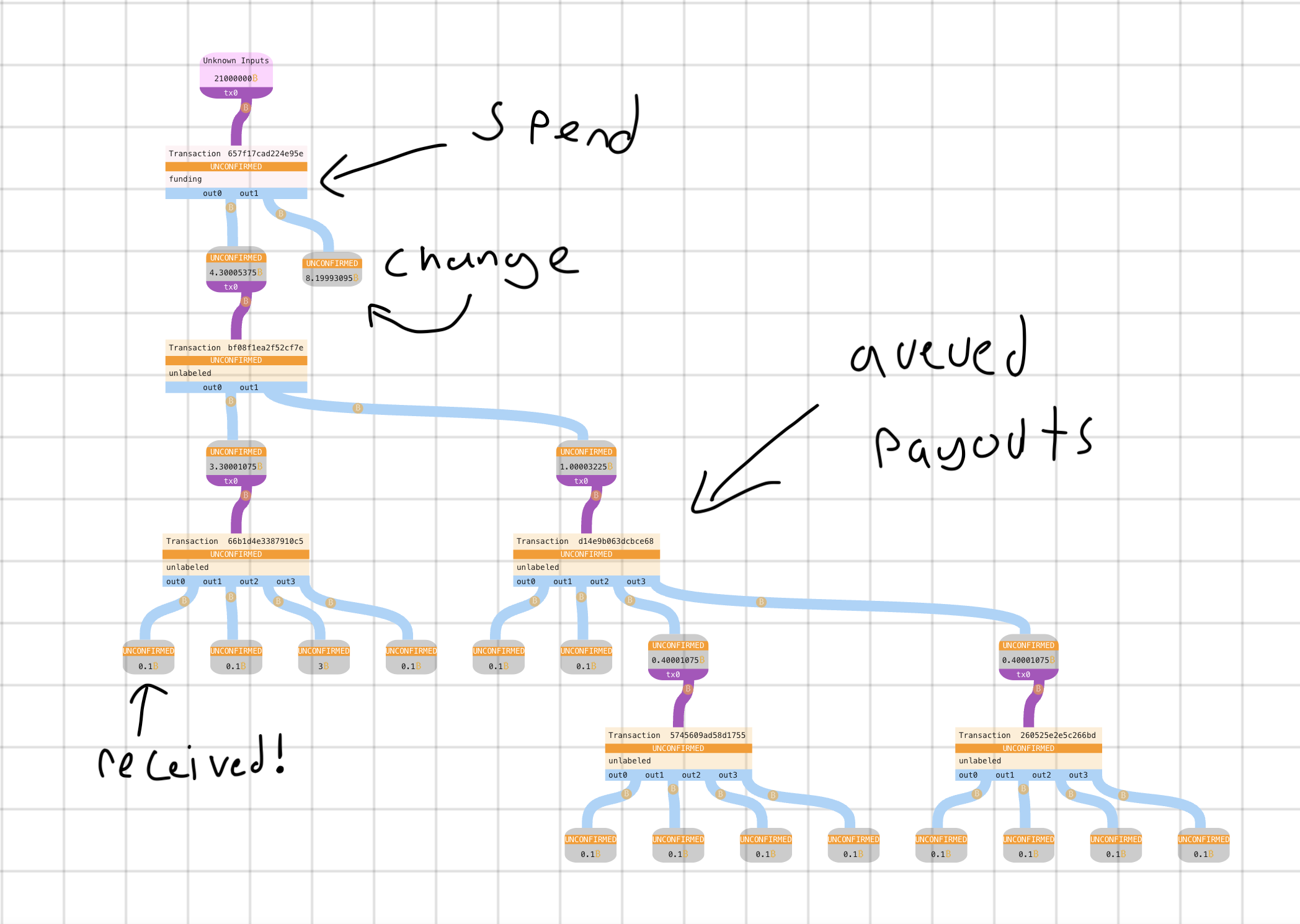

So now what does that look like when we send to it? Let’s do a TreePay with 14 recipients and radix 4:

As you can see, the queuing puts some structure into a batched payment! This is (roughly) the exact same code as above generating these transactions. What this also means is given an output and a description of the arguments passed to the contract, anyone can re-generate the expansion transactions and verify that they can eventually receive their money! These payout proofs can also be delivered in a pruned form, but that’s just a bonus.

Everyone gets their cookie (confirmation of transfer) immediately, and knows they can get their milk (spendability) later. A smart wallet could manage your liquidity over pedning redemptions, so you could passively expand outputs whenever fees are cheap.

If you want to read more about the impact of congestion control on the network, I previously wrote two articles simulating the impact of congestion control on the network which you can read here:

What’s great about this is that not only do we make a big benefit for anyone who wants to use it, we show in the Batching Simulation that even with the overheads of a TreePay, the incentive compatible behavior around exchange batching can actually help us use less block space overall.

Simplifying here – I know Amdahl’s Law… ↩︎